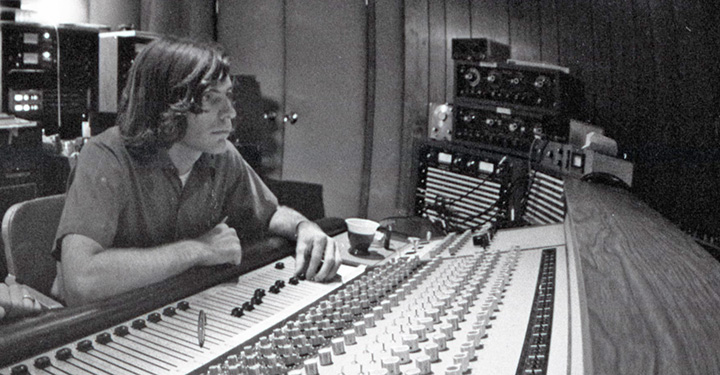

Part two of Van Halen author Greg Renoff’s interview with legendary Van Halen engineer Donn Landee has arrived!

Renoff shared part one of his interview for Tape Op magazine with VHND readers back in September. Now he’s back to make good on his promise to deliver part two.

Below is an excerpt from part two of Renoff’s two-part interview posted to the Tape Op magazine website:

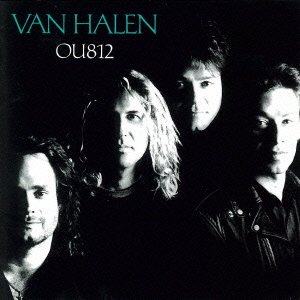

Donn Landee’s lengthy discography is a testament to his versatility and skill as an engineer. Landee worked for T.T.G. Studios and Sunwest Recording Studios in Hollywood before he became a staff engineer for Warner Bros. Records in 1971. Best known for his collaborations with Van Halen and The Doobie Brothers, Landee also logged studio time with artists like Eric Burdon and the Animals, Chet Baker, John Sebastian, The Doors, The Everly Brothers, Jackie DeShannon, Van Morrison, Little Feat, Arlo Guthrie, Montrose, Maria Muldaur, and Carly Simon. More often than not, Landee recorded, mixed, and mastered the albums he worked on in the studio. During his three-decade career, he engineered three Billboard #1 hits: The Doobie Brothers’ “Black Water” (1975) and “What a Fool Believes” (1979), as well as Van Halen’s “Jump” (1984). He also tracked three Billboard #1 albums: The Doobie Brothers’ Minute by Minute (1979), and Van Halen’s 5150 (1986) and OU812 (1988). Part two of this conversation centers on the latter half of Landee’s career, with an emphasis on his work with The Doobie Brothers and Van Halen.

Let’s jump ahead to 1977. Van Halen is a landmark debut album. It’s well known how fast it was recorded, but what was the mixing process like?

Ted and I mixed the album in [Sunset Sound] Studio 2 beginning with “You Really Got Me,” the first single. After listening, I wanted to remix some of them, and Ted said, “Go for it.”

What do you remember about those Sunset remixes?

Over a weekend in October 1977, Peggy McCreary assisted me in remixing some of Van Halen in Studio 1, with the Dodgers-Yankees World Series on TV. We did “Runnin’ with the Devil,” “Jamie’s Cryin’,” as well as a few others.

The following summer, when you were recording the Nicolette Larson debut [Nicolette] at Sunset, Ed [Van Halen] came in and performed a guest solo on “Can’t Get Away From You.” How did that come about?

Ted wanted Ed to play on that song. Ed was eager to play on it, but he didn’t want credit. Initially, and I don’t know if the liner notes were ever changed, but the credits said, “Lead Guitar: ?” Ed played his lead in Sunset Studio 3.

From what I understand, the Van Halen guys all had an agreement not to guest on other albums, hence the lack of credit, but his tone and playing are always unmistakable.

That’s true, it still sounded like Ed.

In December 1978, you and Ted tracked Van Halen II at Sunset in Studio 2. I know it was done in a rush.

Yes, so much so that we didn’t have time booked for mixing at Sunset or Amigo, and we had to go to Westlake Audio.

Okay, we will come back to that. What do you remember about recording the album?

I remember recording “Spanish Fly” in Studio 3. We had to rent Ed an acoustic guitar because he didn’t own one.

The mix and production on “Somebody Get Me a Doctor” is so powerful. It sounds like Ed is playing through about a dozen Marshall stacks.

He always used just his one main Marshall amp in the studio. There was seldom anything more than that.

And just one cabinet?

Yeah, always.

You recorded Ed with Shure mics?

If the mic was right on the speaker, it was likely an SM56 or 57.

You can really hear the room on that track. It also has that trademark Van Halen party vibe.

I don’t think there’s much room sound on “Doctor.” It’s probably delays, along with Westlake’s EMT [140 plate reverb].

What was it like to mix at Westlake Audio? Had you worked there before?

That was the only time I worked at Westlake Audio on Wilshire Boulevard. It was actually their sales office. Tom Hidley, who I had worked for at T.T.G., owned Westlake Audio and they built recording studios. This Westlake office had a fully functional control room. It was used for mixing and demonstration.

I imagine that was less than ideal?

It was a very good room that was a long drive from home. Ted has talked about how small the 5150 control room was; this one was even smaller. On the other hand, I had heard that the first Boston album [Boston] was mixed there, so I knew it could be done.

I’ve seen a few Van Halen acetates, often with different sequences. I know Ted always valued your input. Did you express your opinions on sequences?

I did, but Ted had to sort through it himself. We’d want to give potential singles a chance of being heard, and, at the same time, each transition should feel comfortable and maybe tell a story. It could be complicated, but Ted was good at it.

On the next Van Halen album, Women and Children First, Ed played a Wurlitzer on “And the Cradle Will Rock…” What did you think when you first heard that?

“That’s a Wurlitzer?!?” [laughs] My next thought was, “How’s he doing that?” I went out into Sunset Studio 1 and watched. When he played with his effects through his Marshall amp, it sounded like a new kind of instrument. I loved it.

On “Everybody Wants Some,” once again it sounds like Ed was playing at an ear-bleeding volume. How loud did he play in the studio?

Not loud at all. Ed’s was the quietest Marshall I’d ever heard. What Ed wasn’t telling everybody was that he was using the Variac [variable transformer] to run his Marshall at 85 volts instead of 120. That was one of the key reasons he got that sound.

Did Ed typically adjust the voltage on the Variac in the studio?

No. He’d have it set to between 80 and 85 volts and he would rarely change it. When he’d find something that worked, that was it. There are other musicians that would fiddle around with settings all through the sessions. Not Ed. He would get what he wanted; and when he liked it, it was locked in and he wouldn’t touch it.

That reminds me of the Michael McDonald anecdote about how you’d beg him not to turn knobs on his synth after you’d found the right sound.

Yeah. That’s true. [laughs] Mike loved adjusting the synthesizer. He’d have a good sound, and we’d say, “Stop right there, that sounds great!” and then he’d change it. Ted would say he couldn’t stand it and go into the lounge.

I was surprised to learn that Women and Children First was recorded in all three studios at Sunset Sound.

We would work wherever there was room. Most of the tracks were recorded in Studio 1, many overdubs were in Studios 2 and 3, and all of the mixes were done in Studio 2.

You recorded the sound of a gentle rainstorm on that one. How did that come about?

“Could This Be Magic?” was the only track we ever did in Studio 3. It was raining, an unusual event that year in L.A. Engineer Gene Meros put mics out and we recorded the rain for the song.

On that one, Dave played an open-tuning acoustic and Ed played slide guitar. He never played slide guitar before, but Ted encouraged him to do so. Do you remember this?

Yes, I think that was the first time Ed played slide guitar. Ed and Dave played that together, side by side.

Were the vocals live?

We started running down the song with vocals, but then we decided to get the guitars first then add the vocals. We did the vocals that same day.

There’s always chatter that Ed, rather than bassist Michael Anthony, played bass on a bunch of Van Halen songs. Can you set the record straight?

It was almost always Michael Anthony! I can’t even name one song where I know that Ed played bass. I know it happened, but it was rare. Up until “I’ll Wait,” I think all Van Halen songs were recorded with the entire band playing together.

Fair Warning was the next Van Halen album. That one took longer to record.

It did take a long time. It was my first time back at work since my house was flooded the previous year. Ed and Al [Alex Van Halen] were after something more intense.

I think Fair Warning has the best drum sound out of any Van Halen album.

We were always trying to record Al correctly, and I think we got closer on Fair Warning. Speaking of Al, he hung a black military-surplus gas mask between the monitors in Studio 2, exactly where Kent [Nebergall] had hung his Star Wars X-wing toy back in 1977 when we recorded Van Halen. That gas mask did set the mood for Fair Warning.

You told me that you recorded a cowbell in the Sunset Sound courtyard instead of in Studio 2. Tell that story again.

On “Hear About it Later,” Al said he wanted the cowbell to sound “thicker.” I thought about the way a basketball sounded dribbling outside on Studio 2’s little basketball court between two brick walls. We set up a mic and headphones outside and recorded.

When you recorded “Sunday Afternoon in the Park,” something unexpected happened when Ed and Al cut the track in Studio 2.

Yes. We maximized the “microphonic” nature of Ed’s Electro-Harmonix Mini-Synthesizer by having Ed play it while it rested on a baffle in front of Al’s drums. Al’s kick drums were “keying” the synthesizer. It was bizarre. When Ed went to move it, we said, “No, no, no! Leave it!”

Ed said numerous times that he recorded solos at Sunset for Fair Warning in the middle of the night. Did you have a key to Sunset so you could come and go?

No. Sometimes, when I would have to stay late doing odds and ends, Ed would want to stay and either work on his equipment or play guitar and piano. He said in an interview that we came back at night and did all the solos again. We did not. He didn’t have a car then, so I’d often give him a ride home.

With “Unchained,” did you add the flanger through the board, or did Ed do that with a pedal?

That was all Ed. When they came in to hear back their final take, I asked him about the pitch on the opening riff because he goes a little sharp. He said, “Oh, that’s fine.” I would probably have pursued it further with anybody else, but his tuning and pitch were unsurpassed. But when I hear it now, it still sounds sharp.

During the Fair Warning sessions, you received your one and only request for a hacksaw from an artist.

That was when we were recording a slide guitar overdub on “Dirty Movies.” Ed said, “Get me a hacksaw!” I got one from Howard Weiss or Jim Isaacson in maintenance. I handed it to Ed, and he just cut off a piece of his guitar. [laughs] He couldn’t hit the notes with his slide with the horn in the way, so he got rid of it.

Hats off to the staff of Sunset Sound for having exactly what the client needed to nail the take!

Tutti and Paul Camarata, who operated Sunset Sound, always had great people on staff – everyone from Bill Robinson, who was the studio manager, to the engineers: Peggy McCreary, Kent Nebergall, Gene Meros, and Corey Bailey – they were all top-notch professionals.

Diver Down was the next Van Halen album. Its album cycle was kicked off by the single, “(Oh) Pretty Woman,” and then you guys raced back into the studio to do an album.

Van Halen recorded “(Oh) Pretty Woman” for a single to keep Warner Bros. content, so Van Halen wouldn’t need to record a new album. “Pretty Woman” backfired because it was a hit and Warner Bros. wanted a new record immediately. Again, Sunset Sound was not available, but this time we were able to work at Amigo in Studio E, a fine studio.

Did Diver Down cause a lot of frustration?

Oh yeah. Ed and Al didn’t like all the cover songs, except for “Big Bad Bill,” and nobody liked being rushed again. But they got some strong airplay from Diver Down with “Pretty Woman,” “Where Have All the Good Times Gone,” and “Dancing in the Street.”

I love Ed’s solo on “Dancing in the Street.”

We were working afternoons at Amigo. One morning, around 3 a.m., I was at home asleep and someone was pounding on my bedroom window. I figured it had to be Ed. I let him in, and he said, “We gotta record right now. I just worked out the solo to ‘Dancing in the Street!'” I said, “Well, okay.” [laughs] We drove to Amigo, and, at about four in the morning, we recorded his solo on “Dancing in the Street.” He was relieved to get that done.

“Happy Trails” is a great way to close the album.

I like the demo version of “Happy Trails” we did back in 1977 too. They were at Sunset doing background vocals with all the guys around their mics. We let the tape run and they did background vocals on every song we’d demoed. We got to the end of the session, and I think Ted asked, “What else is left?” Dave [Roth] said, “We do an a cappella version of ‘Happy Trails!'” Ted replied, “Yeah, do it!” They did it in one take, of course.

It was during Diver Down that Ed decided that he wanted to build his own studio, 5150, in his backyard.

Actually, he was talking about that during the Fair Warning sessions. One of the first times I drove him up to his house on Coldwater Canyon, he had me look at the guest house and asked, “Can we use this?” I told him we needed to build something more substantial. We walked beyond the guest house, and he showed me there was plenty of room to build his studio. He’d been thinking about it for quite a while.

Had you previously worked in, or spent time at, a home studio?

In the mid-sixties I visited a session at the home studio of [pianist Rafael] “Googie” René, and while recording Fair Warning, we tried to record Van Halen at Dennis Dragon’s [Tape Op #69] home studio in Malibu. I knew that most people who built home studios regretted it. I decided I would build Ed’s studio for a minimum cost.

After you guys decided to build 5150, you needed to get your hands on a lot of gear. How did you find out about the console at Western Recorders?

Dennis Dragon bought a console from Universal Audio [UA] that came out of Western Studio 3. He told me a nearly identical console from Western Studio 2 was available, so Ed and I went to UA to have a look. I was familiar with that console because I’d recorded some of Ron Elliott’s [ex-The Beau Brummels] The Candlestickmaker on that console in 1970. I said, “What else do you have?” The staff showed us several stereo EMT plate reverbs, and from about 50 feet away Ed liked one EMT which was painted green. I looked it over; it seemed to be the best one. So, for $10,000 we had a recording console and an EMT.

Am I remembering correctly that you rewired the console?

The console was originally built for 4-track. We were going to record on 16-track, and possibly 24-track. That required a good deal of modification. I think there were 24 faders, which was plenty. I don’t remember everything we did to it, but we made it work. We built a new 24-channel headphone mix system and added eight echo return positions.

What about tape machines, monitors, and effects?

We bought a used 3M M56 16-track recorder, the same kind of 16-track machine we used at Amigo. It was obsolete, but it worked. We bought a new Ampex ATR-102 2-track recorder. The only other equipment we bought new were wires and cables, some U 87s, and SM57s. Everything else was used. We found great old microphones, Teletronix LA-2A limiters, and UREI 1176 limiters. We got our control room monitors from Kenny Rogers’ Lion Share Recording Studios. Howard Weiss, who was working at Lion Share, called and said, “We’ve got some monitors that you might like.” I went over and looked at them, and they were wonderful. They were basically the same monitors used at Amigo and Sunset Sound, built by George Augspurger with JBL components, so we bought those for 5150.

I know Howard Weiss helped a lot in the construction process. When did he get involved?

I brought Howard up very early in the process to look at the raw ground. This was after we had determined it would have to be built as a racquetball court. What happened is that the contractor, Ron Fry, using my original design, started redesigning it like a little house. I told him we couldn’t have windows, and we needed a much stronger outer shell. I wanted Van Halen to be able to play at any time and no neighbor would ever hear a sound. Ron eventually said, “Well, we could build a studio almost as big as you want if we call it a racquetball court. That type of structure won’t need any windows.” My design had no windows, and it was larger than what we ended up with. A racquetball court had to be twenty feet by forty feet.

I see. The city of Los Angeles wouldn’t issue a building permit for a windowless structure larger than a racquetball court. So, the building inspector thought the construction project was for a racquetball court?

Yes. We built a racquetball court with unusually thick walls. In fact, racquetball was played at 5150 up until the final inspection!

Was Alex Van Halen involved?

Al was involved in every phase. He provided great moral support and many ideas. Even before we started construction, we scratched out plans in the dirt. Another person who played a key role was Ken Deane, who I’d worked with at Amigo. He worked on 5150 with me and Ed from the beginning.

Starting in the summer of 1982, Van Halen was on tour. Did Ed check in on your progress?

We talked almost daily through the whole thing. I’d tell him all the problems we were having: “The city wants this, we’ve got to do that. And the contractor wants to do something else.” Every time he’d come back on break from a tour, we’d have a little bit more done. It was incremental, but it was being built.

In the fall of 1982, Quincy Jones had the idea to have Ed do a solo on Michael Jackson’s “Beat It.” How did that come together?

I got two calls, one from Lenny and one from Ted. They said that Quincy Jones wanted Ed to play on a Michael Jackson record, and they thought it was a good idea. I knew that the band was not going to like Ed playing on anybody else’s project. They didn’t like it when he played on Nicolette Larson’s record, and they wouldn’t like him playing on anything but Van Halen records. Michael’s previous album, Off the Wall, was a huge success, and I thought Ed’s playing on a new MJ record could be great for both Michael and for Van Halen. When Quincy first called Ed, Ed hung up on him not believing it was really Quincy. After they finally talked, Ed told me Quincy was sending a cassette of the song, “Beat It.” When the tape arrived, we listened. The first thing I noticed was that the song was predominately in a minor key, except for the section they had designated for Ed’s solo, which was in a major key. Ed soloed best in a minor key. I told him we could have them change it, but Ed said he couldn’t tell someone like Quincy Jones how to rearrange the record. I told him he could and should.

Did he work out a solo ahead of time?

Yes, Ed worked out a solo over this original section. But then I asked him to at least think about another solo, over the chorus, just in case. He did.

Then it was off to Westlake.

Yes, the next day we drove to Westlake Audio on Beverly Blvd in L.A. I asked Ed to promise he would talk to Quincy about the change. I had to ask several times before he said that he would. At Westlake, I said hello to engineer Bruce Swedien [Tape Op #91] in the front studio, and then I met Quincy and engineer Matt Forger in the back studio. I went to sit down on the couch and Quincy said, “Where are you going? You’re doing this!” I sat down at the Harrison console and Ed said, “Donn wants to talk to you about the arrangement.” I wasn’t ready for that either, but I told Quincy our plan. After a few seconds looking through his sheet music, Quincy said, “Oh, that will work. We’ll do it!” We couldn’t cut a tape together that way then because they were synching up several 24-track recorders with SMPTE timecode. You can’t cut a tape with SMPTE. We recorded Ed’s solo over an existing chorus with the vocals turned off, and Bruce put it all together later.

Ed made two or three passes?

Maybe five or six. We met Michael when we were playing them back. His first reaction was, “I like the high fast stuff.”

Then you later comped the solo?

Quincy asked me to come in and put the solo together. I came back the next week and made the composite.

It was a solo that made Ed and Van Halen bigger than ever.

I thought that it worked out great. It benefited both Michael and Van Halen.

In early 1983, Ed participated in Brian May’s Star Fleet Project. Did you attend the session?

No, I got rear ended by a motorcycle on Laurel Canyon on my way to the Record Plant. I had to stay at the scene, and I never made it to the session. But Brian did come up to 5150. He and Ed spent all afternoon summarizing what was wrong with the guitars that made them nearly impossible to play. They seemed to hate guitars. Amazing!

Do you remember the first time you rolled tape in 5150?

It was January 2, 1983. Our first night recording at 5150 was Ed on synthesizer and Al on drums; [engineer] Ken Deane and [drum tech] Gregg Emerson were also there. Ed was ebullient. I just hoped I hadn’t spent too much of Ed’s money building the studio.

How did the decision get made that Van Halen recorded its sixth album at 5150?

It wasn’t my idea. I told Ed it was possible, but that we should try one song first, or maybe start with overdubs and see how it goes. Ed insisted we could do a better album at 5150. He persuaded me with the commitment, “We’re not going to puke this one out.” We hadn’t puked out the other albums, but we were going to get this one right.

So, eventually, you and the band persuaded Ted to work on 1984 at 5150. He had reservations about working in a home studio, but he did sign off on the idea. When did you start trying to cut tracks?

It was Ed who persuaded Ted to do the record at 5150; I just assured him that we could do it. We had the “Jump” track before Van Halen’s US Festival appearance on May 29, 1983.

When you started recording, did you have any concerns about the material? At that point, Van Halen was riding a streak of five platinum records.

I wasn’t worried about the music. We had “Jump,” and Ed had much more. I felt good about 1984.

How did Michael Anthony and David Lee Roth respond to working in Ed’s backyard studio?

They handled it well. Dave continued to write these great lyrics. He would arrive in his 1951 Mercury with bodyguard, Eddie Anderson, driving. He’d grab a cassette that I had made for a song; I remember he did it with “Panama.” He’d go for a drive around the city and come back. He’d say, “I’ve got something!” And for Mike it was the same thing. What I wasn’t ready for was that, for some reason, it felt like the success of the album drove everybody apart.

Ted has often said to me, “I know 1984 is especially great because Donn was at 5150 around the clock, encouraging Ed to write and write, getting him to do new things for the record. But it was driving me crazy because I thought we’d never finish the record.”

Ted got that right. Truth be told, the pressure really intensified after we decided to call it 1984. We all agreed that we’d release the album on January 1, 1984. But eventually it became clear that we weren’t going to make that deadline.

One song that bedeviled the band was “I’ll Wait.” Eventually, Michael McDonald co-wrote it. Do you remember that episode?

We had recorded the “I’ll Wait” track, and Dave said he couldn’t come up with any lyrics for it. Ted asked Michael McDonald to have a listen. Mike came into Ted’s office, sang along with our tape, and Ted recorded his singing. Ted played it for me in the 5150 control room, and when it came to the chorus and I heard Mike sing, “I’ll Wait,” I knew that was it! I hit the talkback and said, “Ed! Get in here, you’ve got to hear this!”

The album opens with a short keyboard instrumental called “1984.” Ed once said in an interview that it had been edited down from a much longer recording. Do you remember that process?

I came in the studio one day and I heard Ed playing his synthesizer all distorted through a little Pignose amplifier. I went into the control room to listen, because I had a mic on the Pignose as well as a direct feed. The direct sounded great. I made a 2-track recording of about a half an hour. When Ed came into the control room, he asked, “What are you doing?” I played it for him, and he said, “Wow, how’d you get that sound?” I said, “It’s the direct. You’ve been listening to the amp.”

Eventually you came back to it.

Ted said to Ed and me, “I wish we had a song called ‘1984.’” I said, “Well, maybe we do.” I played him some of the synthesizer recording. He said, “That’s great! But we just need a short intro.” I said, “We will put something together.” Ed and I edited it down from 30 minutes to the 1:08 seconds that became the title track, “1984.”

The record ran late and that caused some friction among Ted, you, and Ed. What happened?

“I’ll Wait” wasn’t done, and there were a couple little things that needed attention. I remember Lenny Waronker, who was then the label president, called and asked, “What’s going on? When will you have it done?” I told him and he said, “Okay, then we can set the release for the first week in January.” That was our final commitment, and we did it. Lenny really helped. We were able to have “Jump” come out on January 1st, and the album a week later.

I know you mastered nearly every album you recorded until Warner Bros. sold Amigo Studios in 1985. For 1984, you had very limited time to get that step completed. Typically, how long did it take you to master an album?

Once I knew exactly how I was going to do it, and I had all the settings, I could master all the “parts” for an album in one day. Figuring out how I would do it could take anywhere from a couple of hours to a week. It was during this period that Ted might have changed up a sequence or two.

“Jump” came out on New Year’s Day. I remember you told me that it was an exciting moment for you when you heard the new song played on the Rose Bowl broadcast.

On January 1, I watched NBC’s Rose Bowl pregame show, which opened with “Jump.” I realized then that the label promo department was really supporting this record!

Fast forwarding to the end of 1984, Dave decided to do a solo EP, Crazy From the Heat, with Ted. What was your reaction to it?

I love that EP. Dave called me at the end of that project and said, “We’re making a video of ‘California Girls,’ and the song’s not long enough for the video we’re doing. Can you come in and edit the master tape?” I went to the video studio and edited “California Girls,” adding another minute to the end.

In the late spring of 1985, the band split. The future of Van Halen was unclear, so you suggested to go work on an Eddie Van Halen solo album.

Yeah, I didn’t know what else to do. There was no singer; Dave was definitely gone. Since Ed had all this material, I suggested we record as if we were doing demos for a solo album. He agreed. It wasn’t too long before he was talking about wanting to have a band again. We started talking about singers, and then his Lamborghini mechanic, Claudio Zampolli, suggested Sammy Hagar. Ed knew I had engineered the two Montrose albums with Sammy, and I assured him that Sammy could sing!

Before discussing Sammy joining Van Halen, I wanted to ask you about the soundtrack work that you did with Ed for Valerie Bertinelli’s TV movie The Seduction of Gina, and Cameron Crowe’s The Wild Life in 1984.

For The Seduction of Gina, we watched a video with some clips of the film, and we matched up Ed’s music to the scenes. For The Wild Life, Cameron Crowe came up to 5150 with a video of the whole movie. There were certain scenes where Ed played along with the film. “Donut City,” from The Wild Life soundtrack, was nominated for a Grammy for Best Rock Instrumental Performance. Ed played all the instruments on both projects, except for “Ripley” from The Wild Life, which was with Al on drums and Michael Anthony on bass.

How did you record Ed when he played bass? I assume he played his Steinberger bass on those projects?

The bass was almost always through his main Marshall and/or direct. He had several basses, and I don’t remember which songs he played with the Steinberger.

Lots of new avenues.

It was evolution. It was growth.

Before Roth departed, did you do any tracking in 5150 with Roth on vocals for a seventh Van Halen record?

I don’t think we got that far along. I was giving Dave cassettes of Ed’s songs.

In his autobiography [Red: My Uncensored Life in Rock] Sammy shares some humorous anecdotes about his first visit to 5150. It made quite an impression on him!

Yes. [laughs] He talks about how filthy 5150 was, and how we just didn’t care what it looked like! Before he came up the first time, we had spent a day cleaning it up, feverishly, to get ready for Sammy. What he didn’t realize is that the studio had never been so clean!

When you and the Van Halen guys started recording 5150, Foreigner guitarist Mick Jones was brought in as an outside ear. Was that Warner Bros. idea?

I don’t know. I thought he was Sammy’s idea.

How did you like working with Mick?

It worked great. We called him The Duke!

One of the biggest departures on the record is “Dreams.” How did that one come together?

With “Dreams” the band recorded it together, but I didn’t think it really worked. I played Ed his demo and he agreed the demo was better. We then recorded a new track with piano, synthesizer, and a Linn drum machine. We played it for the rest of the band the next day. They liked it, so we added everything else. Right before we mixed it, Mick added a part to the beginning of the second verse. He strummed the high piano strings with a guitar pick.

You recorded Ed’s keyboards first?

Yes, Ed played the Steinway, and the synthesizer was MIDI’d off the piano.

At 5150, did Ed do his solos in the control room or out in the studio?

If he played his solo live with the rest of the band, he played in the studio. For overdubs, he nearly always played in the control room.

The album closer, “Inside,” is one of the oddest Van Halen songs ever, in my opinion.

It was a nightmare. I couldn’t understand why they were doing it. I was asking myself, “Do we really need this thing?” But then Van Halen manager Ed Leffler would come in and say, “Oh, we must have it on the album. I’m telling all the radio stations you’re doing a rap song!” [laughs] It took longer to do than anything else on the album.

The video for “Dreams” featured the Navy’s Blue Angels, and it was all over MTV in 1986. Then, as a thank you for your work on the video, the Blue Angels offered you a flight on one of their jets.

The naval officer who was coordinating the video made the offer through the video’s producer, Jim Cross. Jim told me that if I was interested, I could go down to the Marine Corps Air Station Miramar on a certain day and I would get a flight in a two-seater Blue Angels A-4 jet, and I would be put through the paces. I was just bubbling! I went out and told Sammy. He said, “Oh no, man, you shouldn’t do it. We’re right in the middle of this project. We’re gonna need you.” I had to call Jim and tell him I couldn’t do it.

Earlier we discussed your experiences recording Joe Cocker and Van Morrison in mobile trucks. In 1986 you recorded the audio for Van Halen’s Live Without a Net concert video as well. What do you recall about that project?

I remember that the band members, 5150 engineer Ken Deane, and I took an unusual route from the hotel to the New Haven Coliseum. We took the hotel elevator to the basement, got in a limo, and drove along this little underground road into the bowels of the venue. Under the coliseum was a video truck and an audio truck. Ken and I worked in the latter and recorded Van Halen over the course of two nights. Later, in November 1988, during the OU812 tour, Ken and I recorded shows in St. Louis, Phoenix, and San Diego.

Previously you had recorded Van Halen in Oakland in June 1981 for the soundtrack for some live videos.

Van Halen manager Noel Monk and I flew up to Portland, Oregon, to watch Van Halen perform two shows. Immediately following the Portland shows I went to Oakland and recorded the band using the Wally Heider remote truck.

Van Halen’s next album after 5150 was OU812. A personal favorite of mine is “Source of Infection,” which is a classic Van Halen power shuffle.

Intensity! I’m pretty sure it was one take, like most of those things. When they cut the tracks, they were usually very efficient.

You can tell it is a live take with all three guys playing together because in a couple of spots Ed and Al get ever so slightly out of synch while Ed is soloing.

I liked that sort of thing. It’s organic.

There are a wider range of keyboard sounds and textures on OU812 than on 5150. I read somewhere that Toto keyboardist Steve Porcaro was a sounding board for Ed when it came to keyboard technology. Do you remember that?

Not that specifically, but Van Halen and Toto were close. Luke [Steve Lukather, Tape Op #146] often visited 5150. Ed and I went to many of their rehearsals. They asked me to engineer Toto IV. I couldn’t do, but of course Al Schmitt did an incredible job on that album.

Sammy tells a story about how you hung with him at 5150 when he was really struggling to cut his vocal for the album opener, “Mine All Mine.”

He really worked hard on that song. I turned out the lights and I tried to be inconspicuous. I just let him go. Then he nailed it. I said, “Sammy, that’s fantastic!” I ran out and uncharacteristically gave him a hug. I said, “That’s a great vocal.”

After you left the Van Halen camp around 1989, did you take on any other recording projects?

No, I resisted everything. Lenny called and asked me to work with John Fogerty, but I just couldn’t do it.

Most recently, you’ve been working with Van Halen on some reissues, like the 45RPM MoFi releases of early Van Halen and Rhino’s remasters of the Hagar-era albums. What has your role been?

I listen to what they send me and, so far, I’ve approved them. Their mastering and vinyl pressings are better than ever. The latest releases are the MoFi [Ultradisc] One-Step process. It’s hard to imagine a better method of producing vinyl records.

I want to tell you that your career output is truly remarkable; the albums and songs you worked on changed my life and the lives of countless others. I really appreciate you doing this interview!

Well, thank you. I wouldn’t do it with anybody else!