From Ain’t It Bale News:

“Hello, bayyyyyy-beh!”

Sammy Hagar was riffing on 1950s disc jockey-turned pop star Jiles “Big Bopper” Richardson when he let out the banshee wail kicking off one my favorite rock records of the 1980s. One of my favorite albums of any kind, of any time, period.

And to think, 5150 was a record that almost didn’t happen—created by a band that almost never existed.

Van Halen were one of the biggest bands in the world in 1984, their similarly-titled sixth studio album having sold a gazillion copies on the strengths of such hits as “Jump,” “I’ll Wait,” and “Panama.” They’d earned a cool million dollars headlining the U.S. Festival on their previous tour—a gig they advertised with a staged parachute entrance by the band and a unique contest giving some lucky fan a shot at “Lost Weekend” spent partying with the boys for a while. MTV, still a nascent cable channel, was far more accessible in ‘84 than during the time of the band’s previous release, Diver Down. And with guitar god Eddie Van Halen embracing the times by using more keyboards than ever, not only did those unfamiliar with the band start hearing more of his music on the radio, they started seeing more Van Halen in heavy rotation on television. People began putting images to the music; it’s almost impossible to listen to “Jump” and not conjure a mental snapshot of Eddie in his yellow blazer (with black tiger stripes) tapping the guitar solo on his patented lap-prop, or of frantic frontman David Lee Roth doing a slow-motion back flip while wearing red Jockeys outside his leather pants. It remains one of the greatest videos ever, if only because it promoted a terrific pop-rock song and was a no-frills performance film that captured the players’ personalities (even if they were miming to the music).

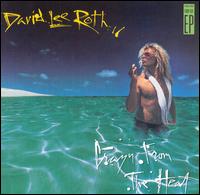

But Roth was suffering from seven-year itch and wanted to keep working following the band’s exhausting world tour. Eddie was in his third year of marriage to actress Valerie Bertinelli and wasn’t as reliable a partner in crime for Diamond Dave, who sunk his excess energy into a four-song EP of covers titled Crazy From the Heat. Roth had been trying to muscle his way into movies but contended himself with the chart success of his versions of the Beach Boys’ “California Girls” and Louis Prima’s “Just a Gigolo / I Ain’t Got Nobody” medley. Videos shot for each track were as colorful as Dave himself, brimming with humor, irreverence, hot girls, and assorted oddball hangers-on. Even his take on Lovin’ Spoonful’s “Coconut Grove” was kinda cool.

The writing was on the wall by January 1985, when Crazy hit record stores. Dave became convinced he’d be at least as successful as Van Halen on his own, so he left. For a time, he was indeed a hot commodity—his Eat ‘em and Smile album was a scorching, to-the-point (30:39) disc of athletic spandex rock and cool covers played by a band of stunt musicians that included Frank Zappa alumnus guitar whiz Steve Vai. Eventually Diamond Dave would lose his luster, what will sales of his 1990s albums A Little Ain’t Enough and Your Filthy Little Mouth selling a mere fraction of what the revamped Van Halen was pushing.

And what of Van Halen?

What was Eddie to do in mid-1985 once he entered his home recording studio on the hill without a singer? The band auditioned several known vocalists, including lady rocker Patty Smythe. Several other names were dropped (including Ozzy and Dio) but not pursued. The demos made during these weeks lacked killer chemistry; there wasn’t a noticeable vibe happening with anybody at the microphone.

Then Edward took his Lamborghini in for a tune-up one fateful afternoon. “Looking for a singer?” His mechanic, Claudio, suggested giving Sammy Hagar a call. The Red Rocker had his Ferrari in for a fix-up. Claudio jotted down the number as the heavens parted and sunbeams tickled the earth.

It made perfect sense. Sammy Hagar, like Van Halen, was already phenomenally successful—a household name in hard rock whose time in Montrose groomed him for later stardom. Like Van Halen, he’d already had a string of strong albums (Street Machine, Red, Standing Hampton, VOA) with chart-worthy hits like “Rock Candy,” “Three-Lock Box,” “One Way to Rock,” “I Can’t Drive 55” and “Your Love is Driving Me Crazy.” Hagar had also demonstrated he wasn’t above doing one-off tracks for movies, or even giving material to other singers who might serve the tune better. For his altruism, soundtrack songs like “Girl Gets Around,” “Heavy Metal,” and (later) “Winner Takes It All” scored big. And Rick Springfield spun Sammy’s “I’ve Done Everything for You” into gold. Like Van Halen, Sammy had a built-in audience. Combining the two musical forces and their fans could be huge.

Risking hyperbole, someone of my generation might suggest the news of Hagar joining Van Halen was like—my Gawd—the biggest news in music ever. But unlike the breakup of the Beatles or John Lennon’s murder, it didn’t exactly make headlines or the six o’clock news. Young teen fans like myself only heard whispered rumors of the alleged merger in locker rooms or food courts at the local mall. This was pre-Twitter; word didn’t exactly travel fast. Indeed, it wasn’t until a month outside the release of what would be the band’s next album that I caught on to what had transpired.

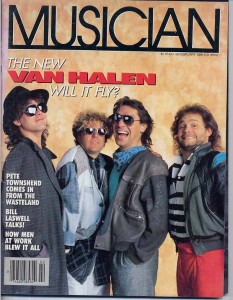

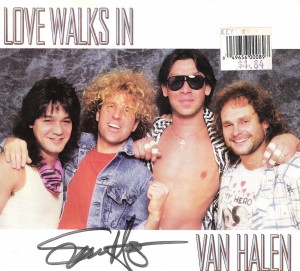

“Who’s that Asian dude?” I asked my buddy while studying a poster behind the counter at a local record shop.

The poster in question was a first look at the new Van Halen lineup; the “Asian” dude in question was in fact drummer Alex, who with his squinting eyes was looking a little more Far Eastern than usual (he’s Dutch). But the real focal point of the group shot was the surfer-dude with the shaggy blonde mane spilling over his Wayfarer sunglasses.

“Is that…Sammy Hagar?” I was incredulous. Excited. Speechless.

Like I said, the combination made sense. Even if it existed only on paper at that time instead of tape or wax. Hagar would bring his own fans to the Van Halen fold. Unlike some no-name singer, Red Rocker was big enough to not have his ego absorbed walking into 5150 Studios. He had persona already—in spades—and wouldn’t have to invent one to front the band. Conversely, the Van Halen boys (and bassist Michael Anthony) would be kept on their toes. They’d have to come up with some cool riffs and hot licks worthy of Hagar’s vocal presence. However humble, a musician of Hagar’s caliber wouldn’t likely put his stamp of approval on something he wasn’t proud of. All of which meant that the first sessions might have been awkward: “Do they like me?” “Is he digging this music?” “Will this work?”

Shortly after seeing the record store poster I came across a copy of Musician magazine at my uncle’s place (he’s a professional keyboard player). The new Van Halen lineup was pictured on the cover, looking decidedly more preppy than it ever had with Roth. A caption questioned, “The new Van Halen: Will It Fly?”

If only they knew.

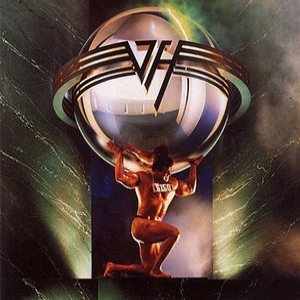

The band even upgraded its logo to reflect their new dynamic. The tri-flared “wings” gracing the VH logo on the Roth-era LP sleeves now curved around, joining behind the letters to form a concentric circle; the wings were now a ring—a symbol of musical matrimony.

I can’t recall whether I bought 5150 exactly on its release date (as I did with every subsequent VH album), but I know I picked it up that March on cassette. It was issued by Warner Brothers, who distributed the band’s early material—but instead of bearing white block lettering on a black spine, the J-card bore a fine red font against a white background. This packaging change wasn’t specific to VH; Warner Bros. had begun issuing other titles with the modern-looking art early that year.

5150 bore one of the most fascinating covers I’d ever seen. Like the new logo, the photograph of an Atlas-looking muscleman shouldering a huge metallic orb was rife with symbolism. The anonymous Hercules (clad only in a Speedo) had been forced to take a knee under the apparent weight of the sphere, which was cracking at the top like an egg, suggesting that something was about to emerge—to be borne. Sure enough, the backside of the LP has a photo of the “hatched” band standing between the halves of the now-shattered globe—peering over the lifeless body of our fallen Olympian. Eddie—who until now favored belly shirts, printed blazers, and shredded jeans—is wearing a wool trench coat over sweatpants and tank-top. His raven hair is still lengthy, but all moussed up. Michael Anthony still sports his trademark razor stubble. Resting a hand on Ed’s left shoulder, he’s wearing a Mickey Mouse tee and pondering something off in the distance. Sammy Hagar appears his left (our right) in what appears to be a denim vest over a red tee. He’s looking downwards—possibly at Eddie, who must have been positioned on a lower step. Alex Van Halen is standing slightly behind Sammy, his face nearly expressionless behind dark sunglasses.

Green means go, and the cover of 5150 is predominantly green (despite the presence of rock’s most scarlet singer). And about that globe. Closer inspection reveals reflections upon its shiny surface, the way one might expect any similar object to mirror its surroundings. The lower hemisphere (beneath the logo) appears to contain reflections of some kind of room—or perhaps the exterior of a building. One can clearly see what looks like three or four vertically-oriented rectangles that resemble—and could very well be—windows. Of course this is just speculation on my part; I’m projecting my own ideas into what I’m seeing. But the best art is supposed to accomplish precisely that; a drawing in of the viewer and a sparking of his imagination. I’m aware the shot of the weightlifter and globe were likely composted together and fixed onto this fantastical-looking emerald stage, and that any reflection perceived therein is probably of an environs that either never existed or was far removed from wherever Mr. Beefcake actually had his photo taken.

But I wouldn’t be writing this little spiel were it not for the music on 5150. Its nine songs (numerically significant—Sammy will tell ya) clock in at 43:02 (whose numbers add up to nine)—but they’re the longest tunes Van Halen had written up to this point. Only “Why Can’t This Be Love” clocks under four minutes. These songs are stylistically very different animals than those bred with Roth. Hagar—who wrote most if not all the lyrics—is comfortable walking in some of Dave’s lascivious, party-hardy footsteps, but not without penning some introspective pieces (at least as far as the genre is concerned). As mentioned, the band had fresh fingers tweaking the knobs in the studio. Edward himself also had some new weapons in his sonic arsenal, not least of which was the Steinberger trans-trem guitar—an axe with a compact, rectangular shaped body and no headstock, and whose vibrato bar would allow the player to dramatically alter the pitches of notes and whole chords without compromising the tuning of the instrument (thus its name).

“Good Enough” commences with Sammy’s aforementioned Big Bopper greeting—which is emulated by a wailing guitar bend courtesy Eddie. The churning rhythm section kicks in following Hagar’s mischievous “Ha!” and it isn’t but a measure or two before we realize, hey, not only will this band rock—it will rock hard and fast. Diehards will recall that 1984 climaxed with the pile-driving “House of Pain;” it simply wouldn’t do to premier the new VH with some wistful ambient music. No tinkling keyboards just yet. On the contrary, “Good Enough” is a crunch, guitar-centric manifesto on the sexual readiness of some “U.S. prime,” upon which—after being rolled over “once, maybe twice”—Sammy will “chow down, down, down.” Fans eager for some link to the past other than the lustful lyrics will note Hagar’s spoken dialog at the breakdown: his bequest to the waitress recalls Roth’s banter from “Unchained” (“You’ll get some leg tonight, for sure!”). I always wondered about some of Sam’s double-entendres. The printed lyrics suggest he says “It’s 3-6-9 time,” which would be in step with his love of numerology. But on first listen I thought—and am still convinced—the Red Rocker is announcing that “It’s sweet sixty-nine time!” “Good Enough” boasts at least one tempo change, with the signature shifting into high gear just prior to Eddie’s solo. It’s so subtle one almost misses it. You hear it and feel it, but it only if you’re listening consciously would your attention be called to it.

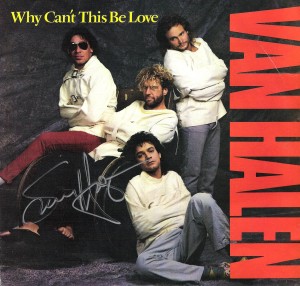

“Why Can’t This Be Love” comes next, giving listeners the fix they’ve been craved after hearing the tune on the radio. Production-wise, it’s a cleverly-crafted tune, what with the percolating sequencer at the beginning and the warbling, almost ominous-sounding, synth creating something of a sonic spine for Eddie’s chords. The lyrics suggest it could have been a ballad—but standard ballads don’t rock like this. But the words did adequately express the sentiment of someone falling head-over-heels for another person who’s giving the cold shoulder: “Oh, here it comes / that funny feeling again/ winding me up inside every time we touch…tell me where to begin / cuz I never ever felt so much.” I still marvel at how Sammy scats along with the notes in Eddie’s lead / solo.

“Get Up” was initially my favorite track on the album. I’d never heard Van Halen play so hard or so fast; it could qualify as a heavy metal number. The opening chords were generated with a little “whammy abuse” on the above-described Steinberger trans-trem guitar, resulting in the couple measure of warble that lead into Alex’s double-kick drums (a la “Hot for Teacher”). Then of course the rhythm kicks in—on overdrive—and Sammy’s first vocal isn’t a word, but a scream. Is he angry? In pain? Is it defiance? The song always struck me as being an anthem of resistance, a track celebrating underdogs everywhere (particularly those double-crossed by love). “Feel like throwin’ in the towel? Don’t be a fool!” Sammy admonishes. Hagar fans will notice the lines referencing one of the Red Rocker’s hobbies—boxing: “Watch the left, watch the right, below the belt…they’re out to knock you out, put you down for the count.” This song also features a healthy smattering of Eddie’s trademark tapping during the solo break. No, he may not have invented the technique—but he sure made it his own. This track is one example of how he did it, and why we love it.

I didn’t care for “Dreams” on my first few listens. It seemed a little schmaltzy, but it’s grown on me over the years. It’s a well-written pseudo-ballad with some fairly inspiring—if ephemeral—lyrics. And it’s also one of Hagar’s best vocal performances ever. “Dreams” is a keyboard-dominated track, but Eddie doubles the main motif on an acoustic guitar at the very beginning and again following his majestic, lofty solo (fitting that the video for the song featured not the band, but the U.S. Navy’s Blue Angels flight demonstration stunt team). I was still mildly afraid of tall roller coasters back in the 80s; playing this song in my mind put me at ease during such rides—even at 200 feet in the air.

“Summer Nights” was my second favorite 5150 tune for a long time (it may very well be my first now). It’s just an unabashedly good-time party song about going out chasing tail with the boys—a fitting subject for a bon vivant alpha male singer who’d just joined a rock band renowned for its backstage revelry. The song commences with a couple deceptively simply chords, a la AC-DC—but Eddie’s playing the Steinberger once again, bending chords in a way nobody without said instrument could. And his solo is actually quite restrained—it’s one of what I call Van Halen’s “snotty-nose” solos, where he seems to be improvising, hitting, hammering, and pulling off at his leisure. It’s not an especially fast track and doesn’t warrant one of Eddie’s blistering lead runs. What the song does warrant, being an ode to summertime fun, are a few high-pitch backing vocals from Michael Anthony. “Summer Nights” is a great example of how the burly bassist helped define the Van Halen sound not only with his thud-staff, but with his inimitable pipes. And that’s why Van Halen will never sound quite like Van Halen without Anthony.

“Best of Both Worlds” is a good rock tune—but musically mediocre by Van Halen standards; never one of my faves. It’s a terrific example, however, of Eddie’s rhythm chops. I’d always imagined he was playing that main lick with his fingers instead of a pick. When the drums and bass join in, it makes for a hefty sound—but it’s still a relatively simple riff. It’s no “Top Jimmy” or “Drop Dead Legs.” In the concert video issued following the 5150 tour—Live Without a Net—the band can be seen doing this little shuffle along with the music. Mike, Sammy, and Ed line up and march to the beat across the front of the stage. It’s an okay visual, I suppose—but it always struck me as mildly homosexual because the guys’ synchronized movements simulate butt sex. I never pondered too deeply on Sammy’s lyrics here, but I suppose one could assume they concern how people can enjoy life here on earth as much as that in the next world (if there is one). “We don’t have to die and go to heaven or hang around to be born again,” he croons. “Just tune in to what this place has got to offer—cuz we may never be here again.”

“Love Walks In” is the big ballad on 5150, and the first tune of its kind where there’s really no argument that it is indeed a ballad—which the Roth-fronted Van Halen never really bothered with. Guitar takes a back seat for this number, which is instead built upon Eddie’s gentle, wafting keys. It’s a good ballad; Van Halen is a talented band, after all—but it seems to exist here simply to demonstrate that the Hagar version of the band is (er, was) capable of getting in touch with its sensitive side when they want to, and whip up a pleasant melody that will please the girls as much as the boys.

The album’s heart and soul can be found in the title track, “5150,” which is a tour de force by Van Halen standards. It begins with—and is maintained by—some of Eddie’s signature staccato guitar rhythm. If “Unchained” and “Panama” were high school, “5150” is the grad school of chops—and this track is Ed’s thesis. Sammy’s lyrics suggest the song is about new beginnings, taking chances, and running wild. Again, it’s fitting subject matter, given this was a “new” rock band in its honeymoon phase. Just a great tune with killer solos and singing (by Hagar and Anthony). “I’ll meet you half the way.”

Album-capper “Inside” is more a novelty track than anything else. One might guess it was constructed from a demo Ed and Alex made sometime before Hagar’s arrival. One can envision Ed searching through tapes for some extra music—even if it were to result in little more than “filler”—and he came up with this throwaway outro. “Hmmph. Maybe Sam can just riff about joining the group, and we’ll talk about what was goin’ on behind-the-scenes around here.” Sure, it’s groovy—and kind of funny—but it doesn’t exactly rock, nor is it a stellar sample of Van Halen guitar virtuosity. Eddie’s alternating bass-synth provides the backbone for a song wherein Sammy jokingly wails about how his joining the group was like a fraternity candidate being subject to hazing. “I got this job not just being myself,” he says. “I went out and bought some brand new shoes—now I walk like someone else!” Eddie’s got a pastiche of guitar parts streaming along in the background, but more interesting are the snippets of band dialogue. I repeatedly listened to the track to pick up some of the buried conversation, which includes studio banter (“I thought it was really gonna be different this time.”) and friendly jibes over fashion faux pas (“Where’d you get that? Out of my wife’s closet”) and money (“Alimony, alimony, alimony!” and “Pay my accoun-tunt!”).

5150. 4 out of 5 fists, baby.